Selling The Shadow, to Support the Substance: An interview with Driely S.

Art — 02.07.20

Words by Anastasia Solovieva

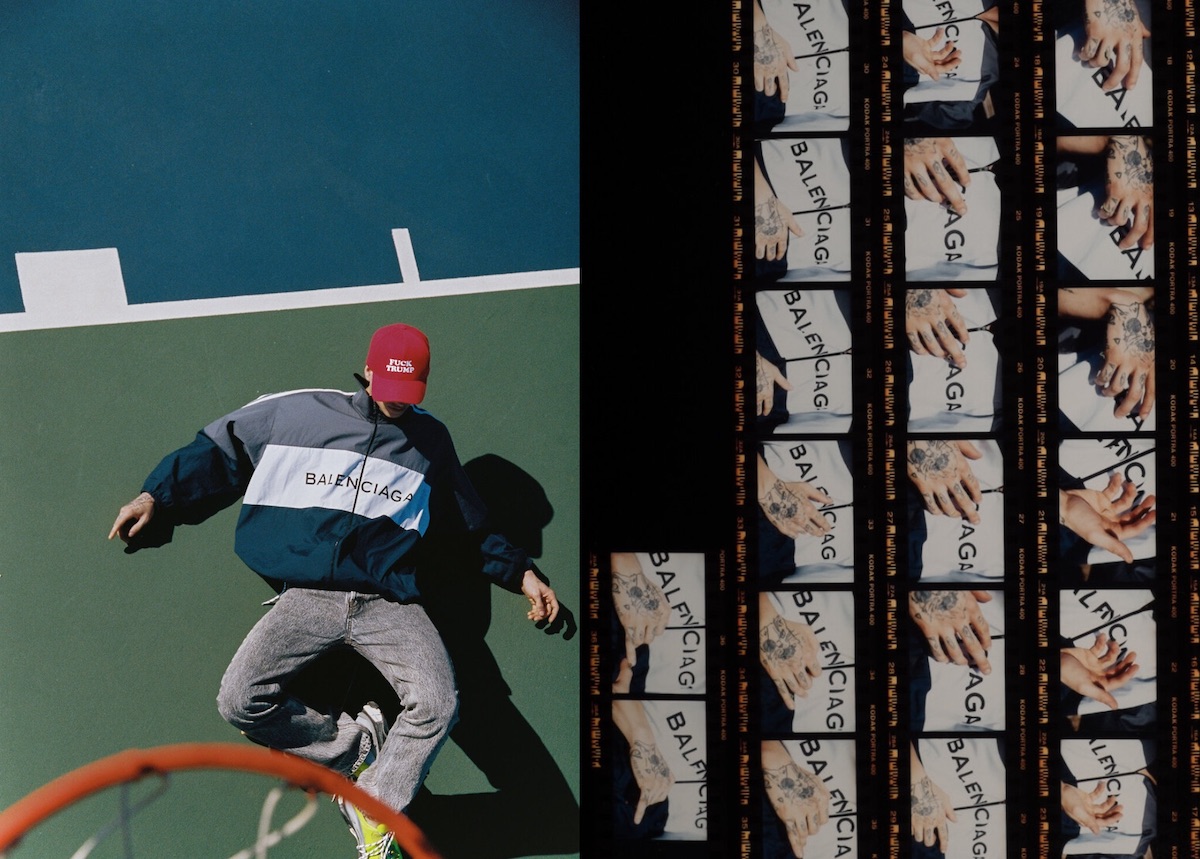

All images by Driely S.

Still from Adidas x Friendly Ghosts, by Nina Meredith.

Photography is an exercise in memory, believes self-taught Brazilian and New York settled photographer Driely S. An unquestionable expectation that anything worthwhile should take a long time, makes her career a rewarding endeavour, only an unfulfilled existence being the greatest fear.

Babysat by a television set most of her childhood, Driely was obsessed with movies. The dream was to move to New York to study filmmaking, but realizing that she can’t afford college, made the first three years in the city brutal. Cleaning houses, cashiering at Target, babysitting, assisting in a hospital and selling calendars at a mall kiosk became the actuality instead. Having no friends, Driely would take a cheap thrift shop camera everywhere she went, out of a real need to document every inch of her existence. She then quickly learnt that it’s never about the camera or the process, but the substance of the image.

Connection to heroes is vital, and the biographies of Italo Calvino and Fernando Pessoa were the supreme companions that taught Driely how to exercise her imagination, always putting things in perspective.

Driely has photographed artists like Earl Sweatshirt, Lil Yachty, Kanye West, Beyonce, Neil Young and Jim Jarmush, working for the likes of Off-White, Dior, Stella McCartney and Burberry, featuring in Vogue, W, and Dazed.

Her work is a pure reflection of who she is as a person, a collection of random little obsessions, dissected into homoeopathic doses. If art is a lifelong chase of the nostalgic feeling from formative years, then as she gets older Driely finds herself exploring deeper the things that used to intrigue her as a teenager. A voyage that persuades to love the practice of criticism, avoiding taking most of it to her rebellious heart.

Adidas x Friendly Ghosts from Nina Meredith on Vimeo.

Produced by Bryght Young Things.

Anastasia Solovieva: You grew up in Rio de Janeiro. How has it influenced you as a person?

Driely S.: We are friendly people by nature. No matter how little we have, we can always find a way to feed another mouth at the table when necessary. But we’re also tough because the socio-political circumstances made us resilient.

Being an immigrant challenges the notion of home. Has it for you?

Travelling is such an essential part of the human experience, and I think once you expand your horizons, it becomes hard to feel like you belong anywhere. You start realizing borders are a construct and that a human being should be allowed to go anywhere and discover new grounds. Anything that will give one’s life a deeper meaning and purpose. In many ways, I do feel like a nomad, and even though home will always be home, there is something about being able to go anywhere and make it your home.

Are you able to pinpoint where the impulse to take photographs came from?

My parents always had video and photo cameras in the house and even though I could barely hold them in my hands, I tried to use them all the time. I was nine years old when my parents had a really traumatic divorce. One day my dad came home, sat my brother and I by the barbecue (I know, very Brazilian!) and burned all the family photos that my mom was in. I became obsessed with collecting other people’s family photographs I’d find in thrift shops. I guess in a way I was assembling my own family album with other people’s memories. By the time I was old enough to afford my own camera, I just wanted to document everything around me all the time. Photography is in many ways just a physical proof that I am here, I exist. One day when I am long gone, my memories will continue through my photographs.

What’s your approach to photography?

I don’t know if I have one. More than any other vocation, being an artist always means starting from nothing. An artist’s work is almost entirely based on self-inquiry and learning how to hone your quirky creative obsessions so that they eventually become so oddly specific that they can only be your own.

Do you remember your first artistic awakening?

As a child, I was always told I was different. Sharp and extremely opinionated, I always got in trouble for questioning my teachers’ authority in classes. I was very socially awkward and most people didn’t know what to make of me. But as I became a teenager and started learning about art, it became really obvious that it was going to be my fate. Being very sensitive, I came to the conclusion that if I could channel that weird anger and energy into being creative, I would be ok.

So, art became more of a coping mechanism.

It gave a purpose to all my peculiarities and personality traits and freed me to be who I was. Authenticity comes from just being who you are. The more you age to become yourself, the more your work will look and feel like you.

And yet, you don’t consider your work biographical.

I’m a big believer in the “Death of the Author” theory. I don’t think my personal life should influence the viewer’s perception of my work. That is not to say that my day to day doesn’t influence the work I’m making. I just don’t think that type of information is relevant to one’s appreciation of the work.

Is there a work of art that made you cry?

The first time I saw a Francis Bacon painting in person I cried because I felt I would never be able to make anything as good as even his very worst work. It felt like a really cathartic moment. I cry seeing a lot of art. Sometimes I smile at art and get angry seeing art. Art should make you feel something, even if it’s repulsive.

What about a movie that changed your life?

I guess if I have to pick just one it would be El Topo by Alejandro Jodorowsky. I first saw it when I was maybe 16 or 17 and experiencing it was like a lightbulb going off inside my head. It completely redefined my understanding of art and made me realize movies are more than just entertainment. It melted my face the first time I saw it. So many epiphanies.

Jodorowsky is a man of such integrity. He takes his time with things and he never sells out. One of the messages I took from his film Endless Poetry is that life has a hefty element of absurdity.

Absolutely. Life is completely absurd. And his integrity is something I truly admire. At the end of the day, your name is your best currency. If you don’t compromise, eventually your name will be all that matters to get people to come to you and let you do your thing. There is great value in keeping your integrity.

Your work has been cowardly copied in the past. How much do you care?

I’m learning to care less. I keep telling myself that if people copy my work, it must be because I’m doing something that is resonating with them. I think being influential means accepting that people will build on the work I’ve made. But sometimes it feels like a blatant rip off, and when it’s used for commercial gains it really upsets me. I put way too much into creating something unique for myself and giving it substance and integrity, that when someone just takes it without asking to make a quick buck, it feels like a betrayal to me.

What is the least favourite part of the artistic process for you?

The loneliness and sadness. Creating involves a lot of pain. Usually, if I’m happy I don’t want to sit down and make art – I’m busy living and enjoying my existence. But at the times I am most down, I tend to make my best work.

.. and what is the part you enjoy the most?

Honestly just being done. Sometimes it feels so painful to birth ideas and flesh them out that it feels like a small miracle when you finally finish. Nothing feels better than being able to get stuff out of your system and bask in the glory of accomplishment. Oftentimes only you can see the work for the work it is. And those are the small internal victories worth celebrating.

Tell me about your current Capitalism is the Virus project, how did it come to be?

I have zero expectations for this series. It started as a way to amuse myself, without overthinking. To give me a reason to get out of bed every day and learn something new so I don’t get depressed over the current state of affairs in the world. Naturally, I was curious how something invisible to the eye could bring an entire system down to its knees. So, the project was born out of my urge to explore ways to visualise the invisible, and coming to terms that the real virus is the oppressive system that has been killing us for a long time.

What are your thoughts on the changes that the creative industry is going through?

The industry has already changed quite a lot within the last six years since I started freelancing full time. It has opened a lot of doors but it has also created a ton of disposable content. I am fully aware that I wouldn’t have a career if it wasn’t for Instagram and how that diversified the playfield. But we still have a long way to go before things level up. I hope once the playfield is fully levelled up we can refocus the conversation on quality of work and less on quantity. Right now it’s all about getting as many diverse voices seen, but with that, there has been an abundance of mediocre work being pushed as profound simply because of identity politics.

I think it’s even more problematic for women, period. We are either too fat, or too thin, too outspoken, or too timid. There is always something. Being women we often just can’t win. You were outspoken recently on your Instagram about that, after posting one nude self-portrait and your audience suddenly activating in a way they don’t for your work.

I hate having my work defined by my sex or race. The problem with identity politics is that it creates a lot of bad work that lacks depth under the pretence of being meaningful. I often get added to these “Best Female Photographers” lists and it deeply frustrates me because we never see lists of “Best Male” anything. The double standard is real. My gender shouldn’t affect how my work is perceived. Ideally, you want people to appreciate the narrative, but my gender shouldn’t be the first thing that comes into conversation when discussing the work. I find that limiting. Hopefully, we are progressing to a point where one day we will be levelled equally with our male peers and we can focus the conversation on the quality and context of our work rather than whether or not we have a vagina.

You took a long break from Instagram. What caused that and what is your relationship with it?

It’s a love and hate relationship really. I don’t mind sharing my creative process but I don’t care for the feedback. Lately, I have been debating deactivating all comments. I wish I could remove all the likes as well. I think ideally it should be like an art gallery. You can go in and look at stuff, have your opinion, but I don’t need to hear what the audience has to say.

It does feel like a bit of an echo chamber. I think we as an audience also need to work harder at questioning our decisions and actions, as it is equally our responsibility to shape the concept of “good work.”

It’s definitely a platform that’s geared towards clout and not the quality of work. So I try to not pay much attention. The best thing I did was unfollowing everyone, that way I can just stay in my lane and not be bothered with that type of constant engagement. I wish photo editors and clients, in general, would go out of their way more to seek new art. I find it unfortunate that the photo industry relies too much on it to “discover” new work. The algorithm is completely detrimental when it comes to truly discovering new things. If I could afford the luxury to not have a social media presence at all, I would be out of there in a heartbeat. Sadly I still get most of my work from people seeing my images there. Hopefully one day I can quit for good.

Is there a shoot that’s especially dear to your heart?

There is a photo I took of Pharrell in India that I think is really good and one of the best photos I ever took. The birds were circling around above his head and it was this perfect moment. I think it really represents who he is as a person.

What has been a key moment in your career, where one decision had a profound effect on your life?

Working with Kanye West, only because it opened many new doors. It’s not every day that you get to travel the world documenting some of the most controversial figures of the music industry. Even though I don’t look at that very chaotic time in my life fondly, I appreciate the opportunities that came from me saying “yes” to that one job.

Do you believe in happy accidents?

I’m all about happy accidents… I think that’s why I love analogue photography so much. You never know what type of chemical, emulsion or any other type of weird accident will make or break an image. And that makes it exciting to me. It’s like collaborating with the universe as you never quite know what you’ll get.

When you are not working, what are you doing?

Frankly, I’m never not working. If I’m watching a movie, or reading a book, or just walking the streets, anything can be used as raw material and inspiration for my art. So everything feels like work. The goal is to make living itself an art.

What’s next for you?

I feel like I have outgrown photography and it has become limiting within the stories I want to tell. I want to get more into fine art and video installation. With some concepts half worked out, it’s now a matter of getting proper financing. I also have a movie I started writing and need to finish.

You can follow Driely’s work via Instagram or through her website.