Bridging the Gap: An interview with director Ricky Staub

Art — 12.10.21

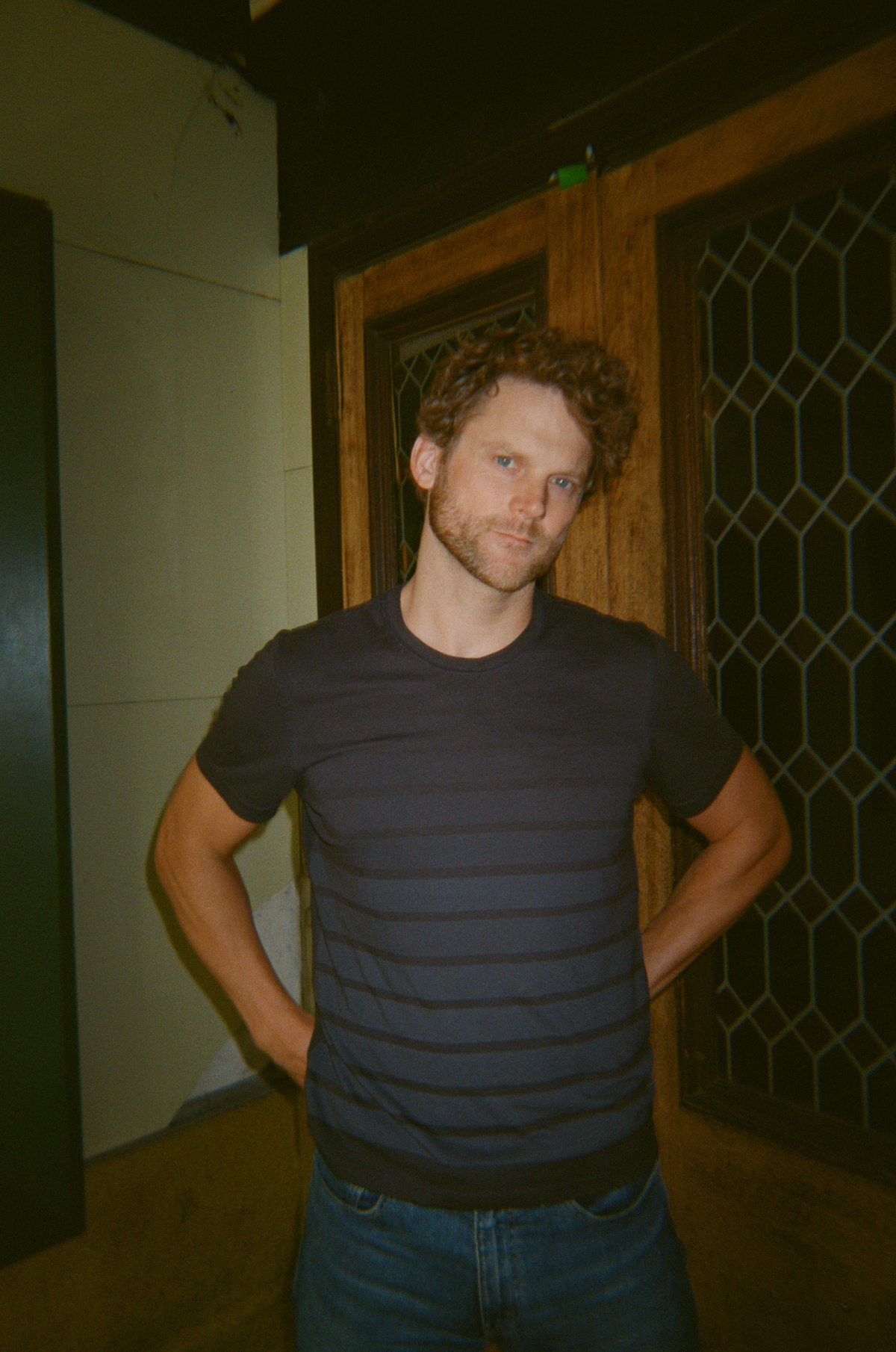

Editor & Photographer: Inbar Levi

Teeth took a drive up to Ventura to meet up with Ricky Staub, the film director, and writer of the atomically successful movie Concrete Cowboy, which came out earlier this year via Netflix. Perhaps his most important mission, though, is almost unrelated to filmmaking. In his own words, Ricky started his film production company because he wanted to help the formerly incarcerated get back on track and give them a chance, to help them train and get work whether it’s within film or any other industry.

Teeth took a drive up to Ventura to meet up with Ricky Staub, the film director, and writer of the atomically successful movie Concrete Cowboy, which came out earlier this year via Netflix. Perhaps his most important mission, though, is almost unrelated to filmmaking. In his own words, Ricky started his film production company because he wanted to help the formerly incarcerated get back on track and give them a chance, to help them train and get work whether it’s within film or any other industry.

Yes, it is far from a complete solution to this infinite problem, but for the lives of the individuals Staub and his crew affected, it made all the difference in the world. It gave them a chance, a shot at restarting a life, acquiring the tools and training, sometimes a social experience that they would have never received if not for Staub.

This could be a movement in the industry, and if to be eternally optimistic, it could be the beginning of something big. Just imagine if more companies in the creative and even noncreative industries took part, giving people the key to a new life. Compassion is rare but still exists and we can only hope that more companies will follow Staub’s lead.

Still image from the film Concrete Cowboy

Your first feature film Concrete Cowboy was released earlier this year with great success, and was acquired by Netflix and starred in all the major festivals. You are at a very dominant point in your career – I’m interested in what brought you to where you are today? How did you become a director? And who are some filmmakers that inspired you to become one yourself?

There are a lot of ways I could answer this question. But the pragmatic answer is I’ve worked many many years in the same direction. I wrote my first script when I was 10 years old. Like a full-on script. Originally I did not want to direct. My ambition was in front of the camera which quickly led to writing which became, and still is, my absolute favorite part of the filmmaking process. My writing partner Dan and I started writing together in 2004 and haven’t let up on the gas since. By the time we first got paid for our writing we’d been writing urgently for 15 years. And I say urgently because we always believed that we were one script away from a breakthrough. We never wavered in our belief in our abilities. When I was a waiter I would work Fri-Sun night shifts so that I could wake up Mon-Fri and write all day. I wanted to build the habits of a working writer. The only thing separating me from the “professional” title was someone paying me. And that’s all that has changed now. Dan and I spent 15 years preparing for this moment and our habits and work ethic haven’t changed.

Films that inspired me were childhood classics we all grew up on. Back to the Future, Goonies, I love classic stories. I love the heart and the laughs they guarantee when well told. I’m not a big cinephile so I don’t know many less mainstream films. A director I look up to consistently is Antoine Fuqua. I love his ability to build worlds that feel immersive and his stories have a commercial drive to them. They hook you and don’t let up.

You’ve mentioned that creating the apprentice program was so important to you that it made you start your own company. Can you elaborate on that?

I started my company in 2011 and I was only in my mid 20’s working as an assistant. There were no companies hiring people who were formerly incarcerated and giving actual career opportunities. My heart hurt realizing that there were folks who no matter how talented or motivated they were, our society had structures in place that would keep them incarcerated well after they had no bars holding them in.

You are mostly attracted to urban gritty and edgy surroundings, those locations help you tell your stories better, and they seem to be almost the main ingredient for your recipe. How did you go about scouting and choosing the locations?

In both my short film, The Cage, and first feature, Concrete Cowboy, I was telling stories that I had lived with for years. In both films, I lived in those neighborhoods so I knew those locations very intimately. I knew the people who lived in those communities very intimately. I don’t know why urban grit attracts me but I love this statement that my composer Kevin Matley said to me once and I think it’s true. He said, “You have the ability to take something others pass every day and mistakenly judge as ugly trash and reframe it so that suddenly it’s absolutely beautiful.” I think brokenness is beautiful. Vulnerable landscapes that tell you their own story. Location scouting is also relationship-building to me. We are all guests as filmmakers and must remember that as we journey into the lives of others and point a camera.

Still image from the film Concrete Cowboy

The film has a very distinct look, mood, and coloring. You can almost freeze any moment or frame and be left with a remarkable still image. How much of the look of the film was controlled by you? How does the collaboration with your writing partner and your DP benefit the film or project you are working on?

That is very kind and generous thank you. I put a lot of focus into the look and feel of my work. I have actually said before that I want to be able to pause the film at any moment and be able to frame the frame. Part of it is just my eye and taste and the way I see things. It’s just in me. But in order to translate that onto the screen, my process begins by sitting down and shotlisting every single shot of the movie. I use a spreadsheet and describe every frame. The end document on Concrete Cowboy was over 80 pages. I get to the point where I can close my eyes and watch the whole movie even before day 1 of shooting. That doesn’t mean I’m not flexible on the day of shooting but the preparation helps me make quicker decisions on the day and know what I want. After I shot list everything I sit with my DP Minka and go through every shot and he juices them up – gives me notes, ideas, dreams out loud with me and uses his talent to make the shots come alive like a painter. Sometimes that means flipping the scene for better light or even deciding, as we did on Concrete Cowboy, that we’re going to shoot an entire scene in 20 minutes because the light is going to pass down the block for that long and it’ll look amazing. Minka is an incredible collaborator and I’d be lucky if I got to make every movie with him. We share such strong visual sensibilities but he’s also a very intimidating storyteller with his own taste so I trust him a lot.

Your casting is pretty unique, you are very interested in real people as actors, but on the other hand, you have someone like Idris Elba, who stars as one of the main leads in Concrete Cowboy. How does this combination of different methods of acting work out for you?

It worked out great. I didn’t know beforehand if it would work but I knew with Concrete Cowboy that this story belonged to the actual cowboys, and well before Idris got involved, we were planning to make this film with only real cowboys. So from the beginning, the work was making sure Idris felt like he belonged in this world and wasn’t just playing cowboy dress-up. It’s here that I learned why actors like Idris and Caleb are where they are – their talent is immense. The way they folded into the community and soaked up their world was so so impressive. And it created really beautiful chemistry on camera.

Does commercialism dictate your artistic direction at all and your choice of projects? If money wasn’t a factor, will you still be making the same type of work and movies?

What I’ve made thus far, I have not had to compromise for money. Money is important of course because we all need it to live and it also legitimizes the work. But at this level of craft, I think if you start making work only for the money then you compromise your voice. It’s a balance. It’s something very new that Dan and I are learning now that we’ve cleared the summit of our first film and are being offered new opportunities.

If you weren’t making movies, what do you think you would be doing? What are your other passions and do you believe that those are also essential supplements to your work as a writer and director?

I honestly don’t know what else I would do. That was part of my process of starting my company is that I really only knew how to do one thing – make stories. But the why of what I do would transfer if I did something else. I’d want to teach or work with folks in need. I see potential in people and things that are otherwise hidden – even sometimes hidden within the person. I’d want to work in a capacity that unlocks that in people. I think that is the heart of my work as a director too. As a director, you are the leader of many people and you need to be aware of just that – they are people. Not just your paintbrushes. They are people who come to work carrying the weight of being human and what I can offer as their director is a place to be safe and a place to push their craft.

You have two locations for your offices, your main office is in Philadelphia and the second is in Ventura, California. The two couldn’t be more different, how does it work for you to have both?

It works great! We have a strong team running in Philly and being out west has been necessary to get the feature / TV arm of our company off the ground.

Still image from the film Concrete Cowboy

This is probably the worst time to be a white straight male in this industry, and in the arts in general, how do you navigate that?

Whenever I am presented with division, my faith has taught me to practice meekness, to move downward and be the servant, to be the listener and the learner, to practice humility, and to practice gratitude. For the greatest gift, we can offer a broken world is sacrificial love.

What is next for you? What projects do you have in development at the moment?

We just sold an original script to Tucker Tooley and Greg Renker who financed Concrete Cowboy. So that will be something upcoming for me to direct. We also have a host of writing projects we’re now engaged on for other amazing directors.

Watch the trailer for Concrete Cowboy below and stay up-to-date with Ricky Staub via Instagram.