A Universal Light: Lothar Wolleh's Vision on Humanity

Art — 26.08.25

Words by Beatrice Sacco

Lothar Wolleh, Suchobeswodnoje, 1955 © Lothar Wolleh Estate, Berlin

In a time of great division and polarization, such is the one we are living in, it is important to remember. We must not forget our humanity, and the humanity that we share with those who we feel are distant from us, or even our enemies. Lothar Wolleh, a brilliant German photographer, can show this to us most powerfully and delicately. His exhibition, The Enemy and his People: Portraits from the Soviet Union, on view at Lothar Wolleh Raum in Berlin, is the perfect depiction of that. Wolleh was wrongfully incarcerated in a Russian Gulag when he was twenty years old. He spent more than 5 years in one of the most hostile and inhospitable places on earth. The prisoners’ camp in question was Vorkuta, in the Arctic Circle, just a few kilometers away from where Alexei Navalny died last year. A place of great hardship, where the prisoners would experience almost no light. But in that full darkness surrounding them, they would sometimes be delighted to see one of the most magical natural phenomena: the Northern lights. In that place, Lothar became a photographer. With other inmates, they secretly built a camera to document their harsh reality, but most of all to escape the agonies of their daily lives. Things for Lothar would never be the same.

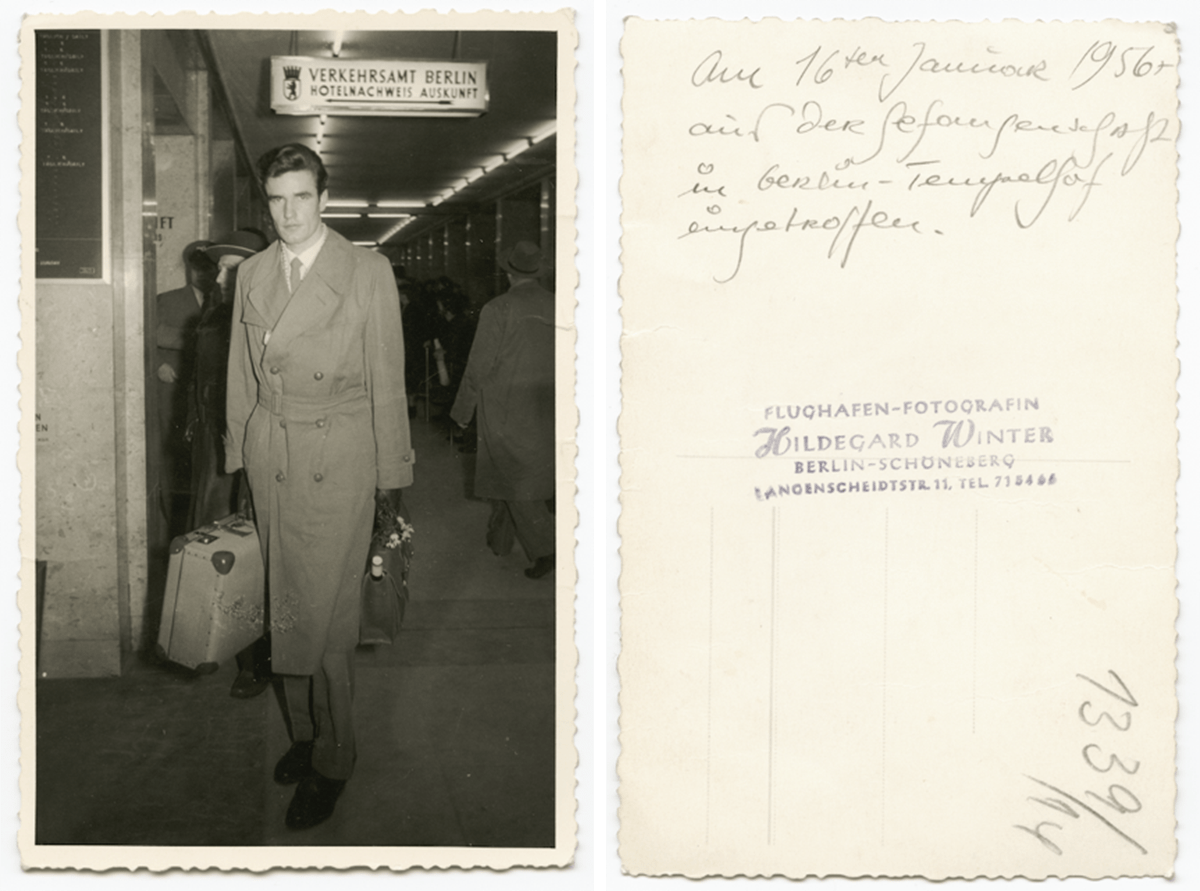

Hildegard Winter, Lothar Wolleh at Berlin Tempelhof Airport, January 16, 1956 © Lothar Wolleh Estate, Berlin

He was released in January 1956, one day before his 26th birthday. We see him arrive at Berlin Tempelhof – an airport that is now closed and was transformed into a public park – portrayed by the airport photographer. He is perfectly dressed, carrying two bags, one for his clothes and one filled with goods. If we examine it with a critical eye, we instantly sense that something is amiss. His son, Oliver, who runs the space and foundation dedicated to him, told me that all he carried, even his clothes, were given to him when he was released, to make it appear as though he was treated properly. The exhibition starts with this photo, paired with two of the pictures Lothar took with his inmates in Vorkuta. We see some wooden huts and a few people walking around. It suddenly comes to mind the difficulty of the situation, and the bravery of taking those pictures, facing possible punishment to document the absurdity of their condition.

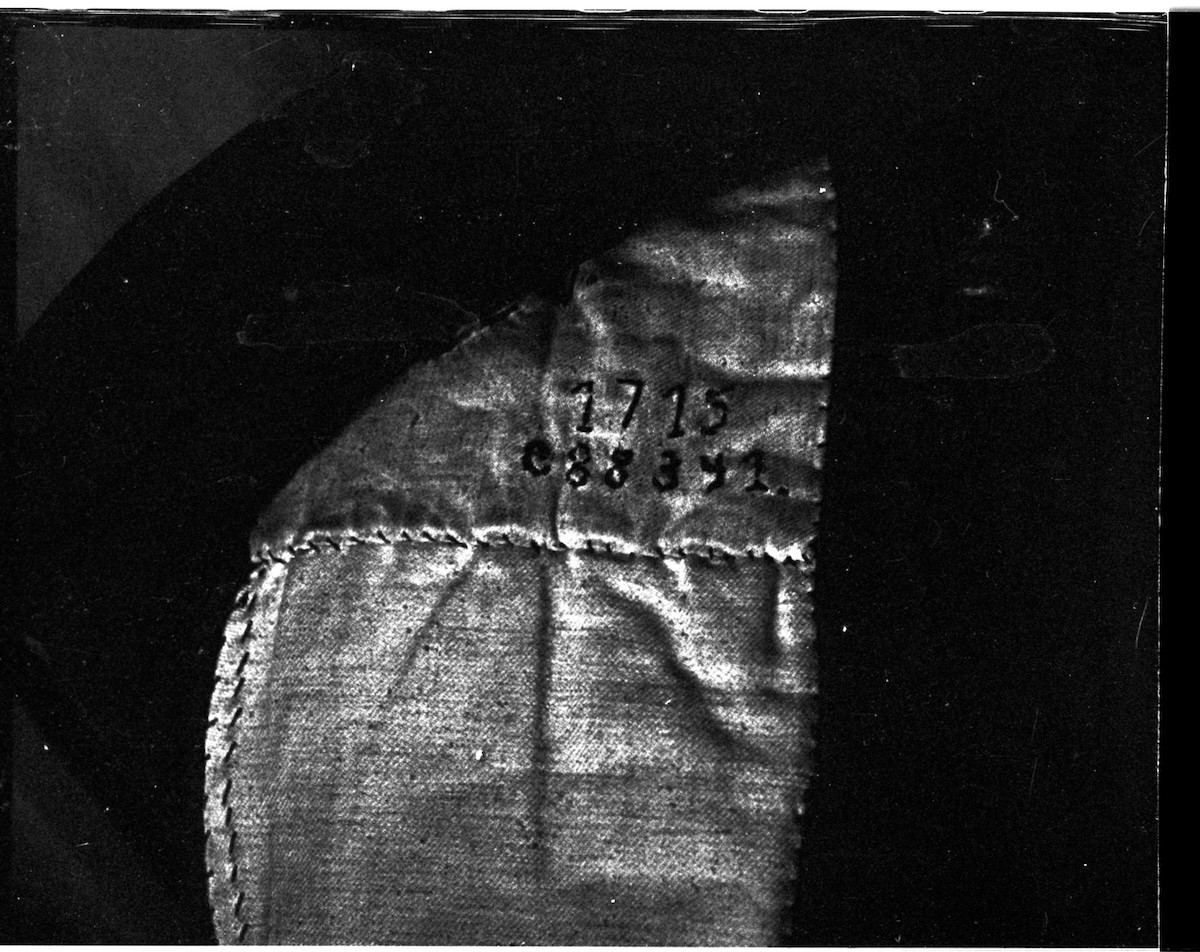

Lothar Wolleh, Vorkuta, 1955 © Lothar Wolleh Estate, Berlin

There is also a picture, not shown in the exhibition, that depicts the prisoner’s number he had inscribed in his clothes, the real clothes he used to wear while being imprisoned. The darkness in that image speaks for itself, but most of all, it speaks for all the people, like Lothar, who were and are wrongfully incarcerated. It speaks of being considered a number, not a person, which is something we see happening over and over again in all the places of conflict around us in contemporary times. We tend to forget people are not just a number: they are, first of all, somebody for someone, a loved one.

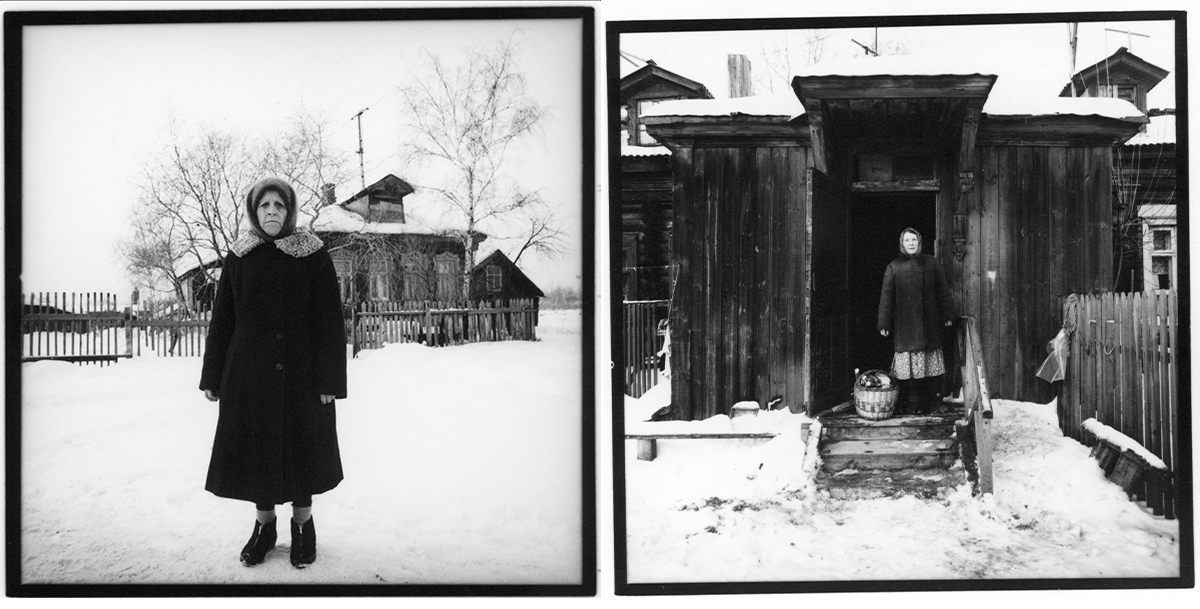

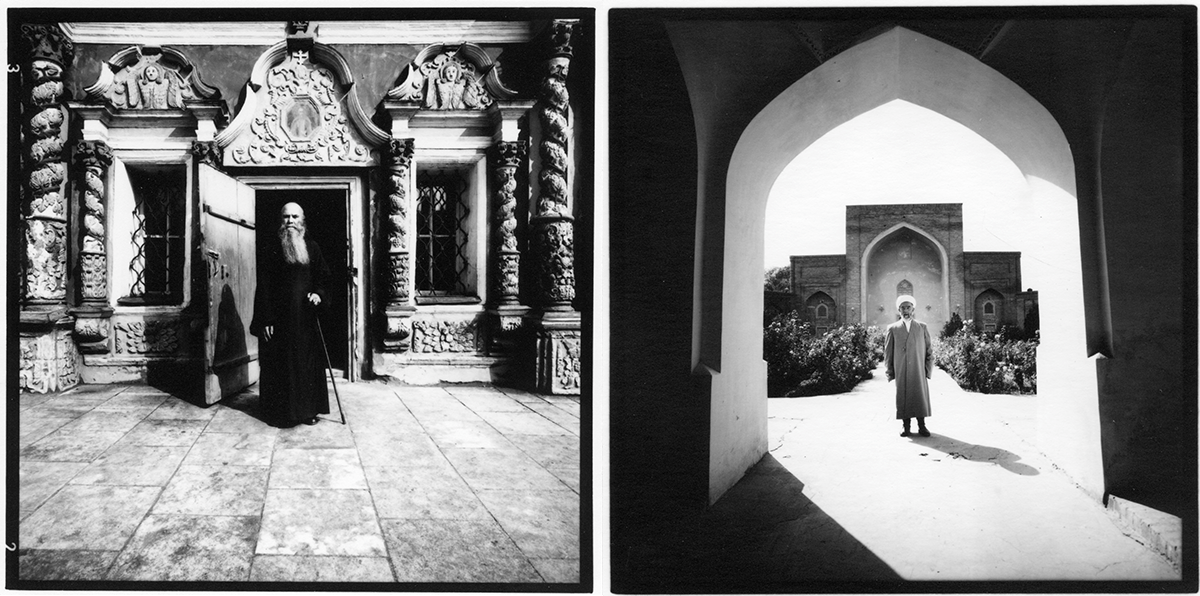

Lothar Wolleh, Untitled, from the series People of the Soviet Union, 1968/69 © Lothar Wolleh Estate, Berlin

Lothar Wolleh, Untitled, from the series People of the Soviet Union, 1968/69 © Lothar Wolleh Estate, Berlin

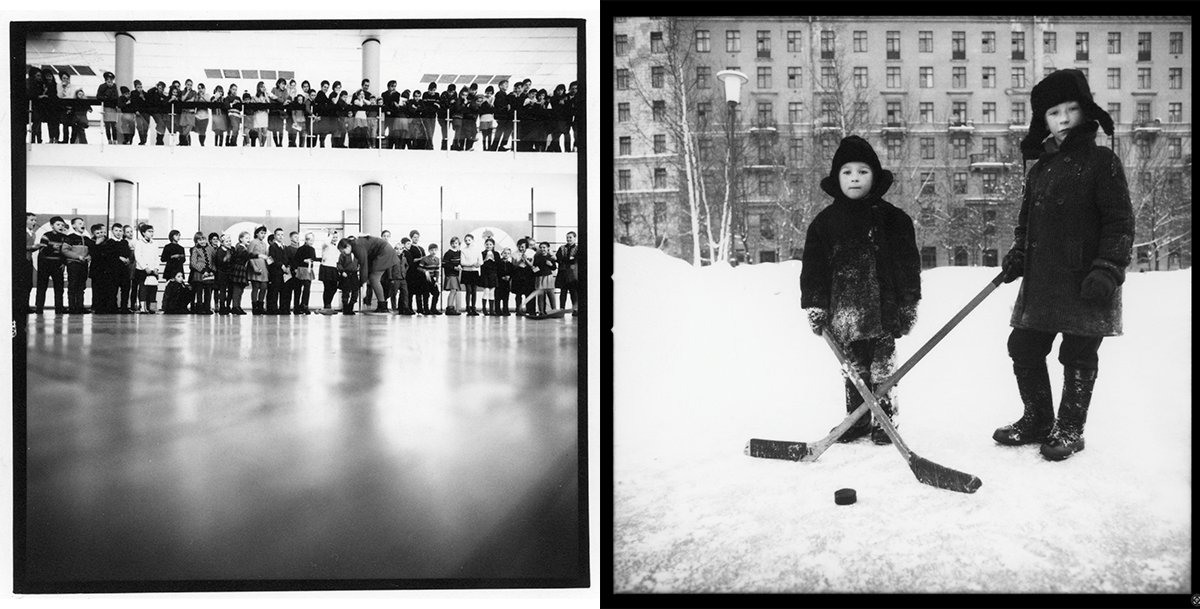

But once he became a free man, Lothar was clever enough to understand that the people who did that to him were not all the people in the Soviet Union. He had the clarity to separate the negative part from the general population. And so, he decided to go on a trip to the Soviet Union in 1968. At the height of the Cold War, he traveled the whole country and decided to focus his lens on its people, from as many different backgrounds as possible. He walks us through hospitals, schools, fields and presents to us the reality of the Russian population. Life might have been different, harder in some ways, but the country has developed in many senses like all the others, and its people show a strength and a tenderness in their faces that remains stuck in our memory. They are like us, yet different from us, surely experiencing the same variety of feelings that all of us do. It is a bridge across time and space, to show and understand humanity in its essence.

Lothar Wolleh, Untitled, from the series People of the Soviet Union, 1968/69 © Lothar Wolleh Estate, Berlin

Particularly interesting are his portraits of religious representatives. Wolleh’s connection to spirituality marked his whole career. He was never affiliated with a particular religion, yet he was drawn to a representation of spirituality in all its shades. It becomes particularly striking in a time as that of the Soviet Union, when religion was strongly limited and persecuted. These portraits, which he will then continue all around the world, are another powerful legacy, and present an image of the country that seems different from the widely spread news that the West receives. The concept of enemies becomes blurred if one stops and notices the shared humanity that lies within all of us, the common life experiences, the hopes and fears, the struggles that all of us face as human beings. As a person who got to suffer directly because of that country’s policy, it is a huge act of depth, of maturity, and understanding. Lothar never stopped at the surface; he dug deeper and deeper.

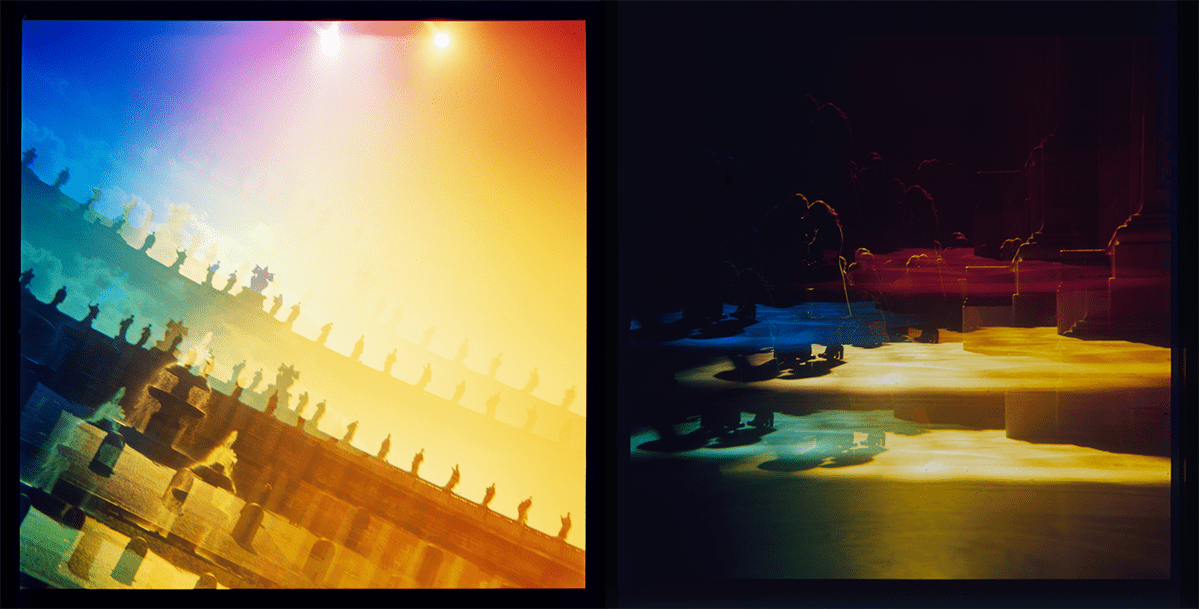

Lothar Wolleh, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican, 1974/75 © Lothar Wolleh Estate, Berlin

One of his most beautiful series, which never got published, is dedicated to his powerful connection to spirituality. It is realized in the Vatican City, but nothing in the pictures reminds us of it. The main focus is his research is on light, specifically on the layering of lights. This research reconnects deeply to his past as a prisoner in Siberia, where he got to witness the Northern lights. That magical phenomenon became a sort of obsession for the photographer, who used throughout his career many expedients to recreate them. The colors of the rainbow now appear inside Saint Peter’s Basilica, and their mystical spirituality covers everything. People lay in the darkness, touched by this powerful and magical light, invisible to the building and to its passers-by. But he makes it manifest to us, the silent witnesses of this past moment.

Lothar Wolleh: untitled, 1968/69, from the series “People of the Soviet Union”, 1968/69, gelatin silver print on baryta paper, 9 x 9 cm © Lothar Wolleh Estate, Berlin

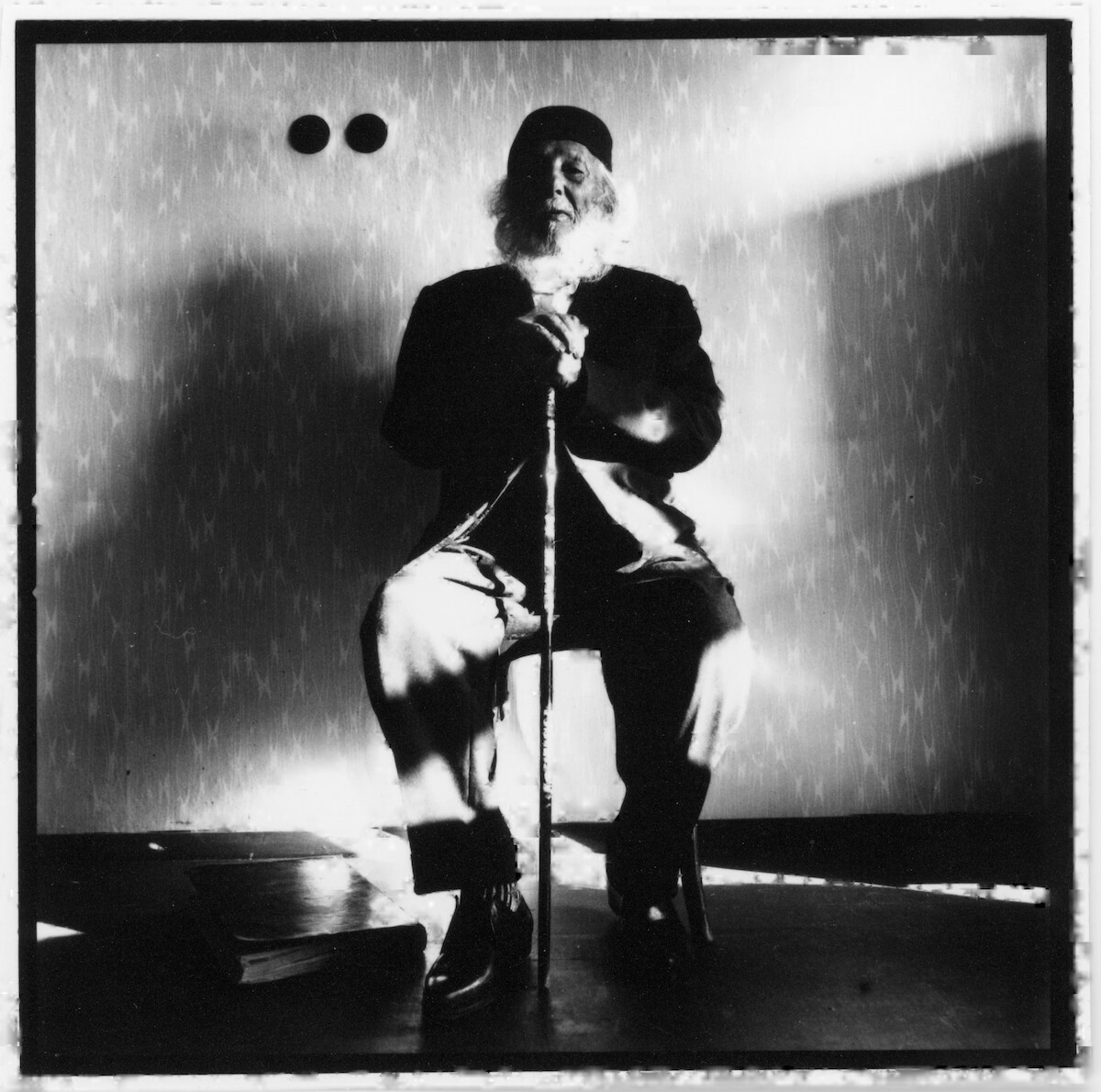

Life is always a journey that takes us back and forth, from where we started to where we are going, to the roots of our personality and the things that impacted them, and back again. Lothar’s journey and practice depict it most powerfully, taking us to unexpected places, merging light and darkness in a powerful balance. The exhibition also walks us through all of this, to bring us back to where we started, with Lothar himself. It ends with a self-portrait of the artist, who appears enveloped in the darkness. The picture lies on the opposite wall of the picture taken of him at Tempelhof airport, again as a free man. Oliver, his son, told me it became a pretty common thing for his dad to have his self-portraits staged in the dark. The reason? The artist had probably lived through so many harsh and negative things in his short life that a bit of that darkness stuck with him. In his search for light, he kept a space for darkness. And so in his work, it is the light that rules, but in self-portraits, it is the darkness that often reigns. It is a powerful reminder for our journeys as human beings living in troubling times, a memento of the importance of keeping space for both sides, inside and outside ourselves.

The exhibition is now open at Lothar Wolleh Raum in Berlin until December 15, 2025.

Find out more about Lothar’s work on: https://www.lothar-wolleh.com/en/