Art and Textile Politics: An interview with Author and Professor Julia Bryan-Wilson

Art — 04.12.17

Interview by Nan Collymore

Photo by Mel Y. Chen

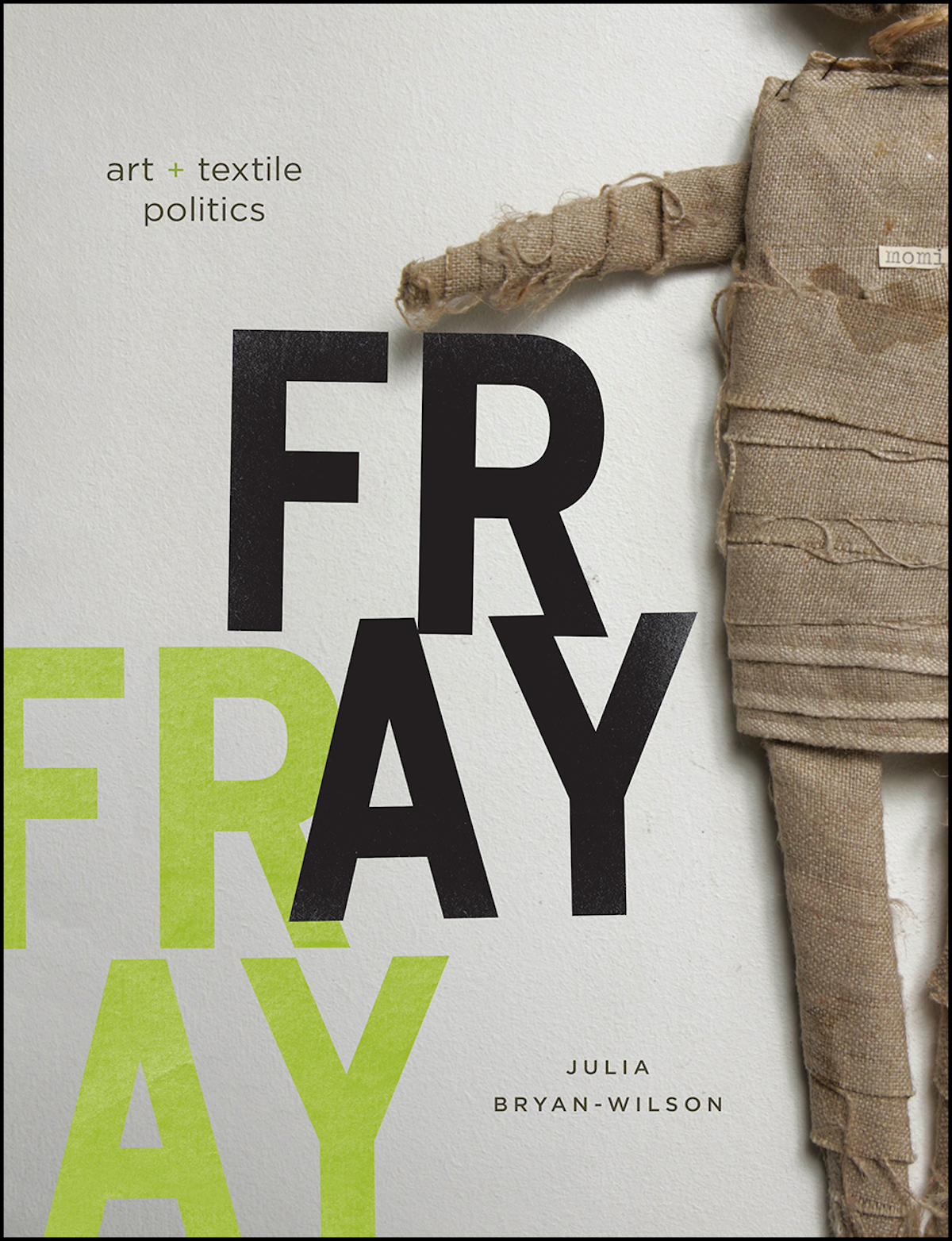

Julia Bryan-Wilson is a Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art in the Art History department at UC Berkeley. She has published many books and is a prolific Writer and Researcher. She has had a busy year co-curating a show about Cecilia Vicuña, publishing Fray: Art and Textile Politics and appearing at a number of high-profile engagements. We had a conversation recently about her beautiful, engaging, and accessible book Fray. In the book, she writes about various aspects of textile wearing and making from San Francisco-based gender non-conforming the Cockettes to the revolutionary tapestries of Chilean Arpilleras. The book is an illuminating, and at many times, personal commentary on the political and artistic significance of textiles.

Nan Collymore:

In your introduction, you talk about your interest in textiles, and its relationship to the high/low and the 21st century’s explosion of artisanal, crafty, hobby-making. Do you think these forms of craft-making could be seen as a way of redressing the language of art markets and institutions?

Julia Bryan-Wilson: Yes, I think so. It makes sense to me that people would have a reaction formation to the aggressive marketing of art, especially in its more outrageously-priced registers, such as $450 million for a DaVinci, and all of these record-breaking prices. Yet, at the same time, many artists have a hard time paying rent and living — they’re adjuncting, scrapping together things as they can. Whenever there’s ever one really extreme movement, it often spawns a bunch of counter movements. To me, it seems trenchant that people turn to hand-making or much smaller scales of making and intimacy in this moment of really high priced artefacts.

I’m thinking about how feminist theory has sought to re-arrange categorisation and institutionalisation, e.g., when you cite Stephen Knott’s example of amateur ‘craft constituting a spatial-temporal zone in which these structures can be stretched, quietly subverted and exaggerated.’ How do you think we can create these spaces of inclusiveness?

I don’t know if I have an answer. I do see the alternative, experimental spaces trying to make those connections and create more inclusiveness. My partner, Mel Chen, is part of a queer people of colour art collective where they present their own work to this extremely limited, but extremely nurturing audience. It’s important to recognise that art might address multiple publics, and this is a feminist idea of course. So there might be bigger, wider audience for what one makes, but maybe what’s more sustaining are these micro spaces and micro audiences, including your own tight circle of friends. It seems crucial to be aware of all of the multiple sites that work can circulate. It doesn’t always have to be addressed to the widest possible mass, and in a way, it could be more interesting or more critical or personally rewarding if you say, you know the truth is, my audience is just these six people, and that’s what I care about. But I think the question of how to really make room for all kinds of makers within institutions is still fairly unresolved.

There will be different routes.

Yes, and different spaces.

I’m wondering about the recurring motif of blood in Cecilia Vicuña’s and Liz Collins’ work and the significance of it, especially concerning gendered bodies. I’ve been making the quipu-like thread work for a number of years, and this work is definitely a response to my own perimenopausal state and a discourse on adolescence/ ageing.

Blood, menstruation, cycles: these specifically female bodily processes were fundamental in 1970s feminism and for the artists that explored that terrain. Then it really fell out of fashion, due to claims that it was essentializing. Everyone wanted to get away from biology. I think that for menstruation to be so inadmissible contributed to more shaming. Bodies are messy and leaky and it’s important to have a visual conversation about that. One way to have that conversation is through textiles since thread and blood have long been understood as analogous or metaphors for each other. Vicuña to me is not an essentializing artist; she does not make claims about a specifically female gendered body that is discrete or that she polices in any way. But it is still unusual, in 2017, to go to an international exhibition like Documenta and see a piece that is about menstruation front and centre. It’s somewhat surprising that there hasn’t continued to be a hugely robust discourse about something that is so fundamental to life, death, regeneration and reproduction as well as bodily shame and abjection. Menstruation is also fundamentally about age, as you just said about your work because it marks these phases of how some bodies move through time . Regarding ageing and obsolescence, textiles are also a very potent medium through which to convey unravelling, fragility, and rupture. In fact, this is a Liz Collins sweater that I am wearing right now (she points to the holes in her sweater), and it’s falling apart. I have had it for more than ten years, and it’s been literally loved to death (we both laugh).

What was your approach to the Trans relationship with textiles for the book?

In writing my text on the Cockettes, I realised that trans wasn’t necessarily an operative word for them at that time in the early 1970s; rather, they used words like drag or camp or genderfuck. I embrace all these vocabularies that signify a move away from strict gendered norms. Yesterday morning I had brunch with a friend who has a child who is not operating within a male/female cis-gendered binary, but I’m not sure that trans is the most appropriate word for them either. It’s gender-non conforming, for sure, but maybe we are still searching for the right terminology and kids like hers will lead the way as they invent new ways of being in their bodies and in relation to the world.

What language do you think we might use to reference blood in Trans-women’s artists work, e.g., Tuesday Smillie’s work ‘Labwork’, ’We ain’t got shit’ and another piece ‘Untitled’, 2008 where they use red thread and sewing tools in a self-portrait.

Well, blood is not owned by any one gender. It can be about violence but it can also be about sustenance. Not only that, it’s something that connects all humans with non-human animals. Your thoughtful question makes me think of Ana Mendieta who used blood a lot in her work. In her ‘Moffitt Building‘ piece she poured blood on a sidewalk as an experiment to see what would happen—and eventually, someone comes along and cleans it up. Later in her career, she made a lot of work that explicitly evoked female gendered bodies, but in this piece, it wasn’t necessarily a woman’s blood or even human blood. It could have been from any animal.

But there was shame attached to it.

Yes, because blood in public is often a shock and signifies that a body – whatever kind of body it is – is not under control, has not been properly disciplined, or has been violated and had its boundaries transgressed.

Could you speak more to the idea of humour as a feminist project, especially with regard to Vicuña’s ‘Precarios’?

These works are so clever and witty. Her juxtapositions of materials are so unexpected and do make you laugh, partly because they thwart expectations about her use of mostly organic found objects. The ‘Precarios‘ are quite heterodox and in a way irreverent about the “natural” world, like when she puts a delicate leaf next to a cartoony pencil eraser, and the results are these surprising combinations that are not at all sacrosanct about the lines between the human-made and the “natural.” She can also be pretty scatological, and that realm is always a source of humour. One way to normalise what is embarrassing or difficult is to laugh at it. For me that is a profoundly feminist project; it is a political strategy to claim and re-signifying these things that have long been sources of shame or humiliation and, say, actually, this is funny.

In that same show in the Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans, those huge unspun fibre extrusions.

Yes – her ‘Quipu Visceral‘ – and the colours are so beautiful, but they also conjure up an image of guts unfurling! (we laugh)

And this made me think of the recent Anna Maria Maiolino show at the MOCA as well.

Maiolino’s work with ceramics imparts a sense of biting and shitting and grabbing, and as she combines the edible with the disgusting with the tangible, these associations come together in a super witty way.

Have we moved on from that movement of producing work that is about bodily emissions being essentialist?

I hope that we have moved on, but patriarchy and especially hetero-patriarchy appears to be unbreakable, especially at the moment. It feels terrible.

Politically speaking, I wonder though if this is the furthest right you can get and maybe people will be more aggressive and abrasive in their oppositional activities?

Let’s hope so.

That makes me think about what you called the ‘gendered injustice and environmental injustice post-Katrina’ in Vicuña’s show in New Orleans that you co-curated.

Yes, regarding environmental injustice, we wanted to highlight how Cecilia’s work across many media has long been in conversation with questions of coastal erosion. The capitalist exploitation of resources, and the plunder of indigenous lands – much of the work in the exhibit in New Orleans related to the precarious sea, to environmental destruction, and also to the possibility of creative regeneration.

I’m interested in the recurring themes of vertical and horizontal in your work. You mention it in relation to Harmony Hammond’s Floorpieces and Rauschenberg’s bed, and in Vicuña’s quipus. Can you expand on this?

It is so fundamental to how we orient ourselves. Let’s say a person is trying to decide how to hang a rectangular canvas. Within the conventions of art history, if it is hung vertically it refers to a person, and if it has a horizontal orientation, it refers to a landscape. There is a kind of internalised perpendicularity we have in relation to the ground, and I’m really interested in how that might become skewed or re-oriented. In Fray, I wanted not only to blur the high/low art distinction but also to rethink the upright versus the low in terms of how we might reconsider the primacy of verticality. There is a show that’s being organised at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum of Hammond’s work where the Floorpieces will be on the ground, and there will be a balcony over them so you can view them from above, which will be fantastic. Her floor-based work makes you question the normativity of your own gaze because you can never quite get a grasp on them — even if you were able to stand on one, you would see your own feet as you looked down.

I like your thoughts on the three strand braid in her work – I like the idea of the three strands standing for a ‘radical queer “third space”’. But I also wonder about the dominant, Judeo-Christian use of the three-the father, Christ and the holy ghost. Could you speak to that, specifically to Hammond’s use of the braid?

Yes, of course, that makes a lot of sense. I’ve felt the restraints of binary thinking, so for me, Hammond’s invoking of a third space has the potential to take us out of a conventionally polarised realm of gender. But of course, the Trinity is an example of something many of us have grown up knowing that is in its own way very conventional or dominant. It is one of the incredible paradoxes and impossibilities within Judeo-Christian traditions that we’ve kind of assimilated or understood to be “normal” when they are absolutely not. My mom is a minister (though I am an atheist) so it is funny that I hadn’t thought of it in that way before your question.

I’m curious about your inclusion of the Freudian notion of the braid as a compensatory tool to replace the phallus. I like how you bring the symbolic into real life, but kind of comically comparing the idea of how textile workers use their hands with a queer woman personal ad. So, I wonder about this idea of the replacement phallus, because in communities that use textiles, or braid, or weave, these activities are very much a part of a feminist project of building a community amongst women.

For Freud, braiding has been persistently feminised and even sexualised. Freud’s theories of lack, and his assertion that braiding is women’s one contribution to the world – it’s so extreme and ludicrous but for me also useful. Braiding has been a resource, as you suggest, and an activity that women turn to that creates intimacy, like a woman braiding her daughter’s hair. But many different types of women have used braiding for many purposes and it is not always in a maternal or intimate vein. I definitely wanted to honour the feminist humour of Hammond’s own practice when I talk about the braid as a replacement phallus. Also, when I discuss the photograph that I found of young African-American women braiding rag rugs, I wanted to emphasise that Hammond wasn’t just citing white middle-class culture in her use of braiding.

I love the chapter on the AIDS quilt making. It was such a hard time and I think I found that the most moving chapter.

It was sometimes emotionally hard to research because I was re-immersed in tremendous loss and death. As I say in the book, my best friend’s Dad and many other people that I knew died of AIDS; it was a very big part of being a teenager in the 80’s. In a way, the AIDS Quilt can’t help but be inadequate to express all that loss, but on the other hand, it does perform a function. It was quite intense for me to revisit all those losses. For example, I had never spoken to my best friend before about making a panel for her father. That was an entirely new conversation even though we’ve known each other for more than thirty years. It was extremely moving for me to feel like I was honouring him by writing about him in that context. My queerness has always been bound up with danger and risk. Not only because of AIDS, but also because I came out of the closet at the age of fifteen, and in Houston, at that time there was a lot of gay bashing – gay men were beaten to death just blocks from where I went to high school.

Textiles often exist at a place between private and public – ‘a queer place that transgresses the border between the sites of erotic activity and art-making’. I love that phrase so much. Can you elaborate on that theme?

Something that I’m always astonished by is how each of us undergoes the simultaneously private and public performance of getting dressed. Every day we choose how to present ourselves there are so many codes we are trafficking in – a million different significations are happening on our person at every moment. I look at this sea of people wearing clothes and marvel at how everyone has decided to wear those particular things. Textiles are next to our skin, and they are with us from the day we are born until the day that we die. I don’t want to be a textiles exceptionalist and say that there’s something totally unique about them, but there is no other substance that we have such an intimacy with, except maybe food or water. But food is intermittent and we just have a very different relationship to it than we do to textiles in terms of how cloth interfaces with our bodies and tells people about our own desires, and material circumstances, in a glance. Textiles are ubiquitous; nothing could be more seemingly normal than our relationship to textiles. But in Fray, I wanted to try to make them strange again. It was also important to me to write that I’m not the expert in textiles— rather, we are all experts in textiles. We all have a profound relationship to them. I wanted to activate a queer method — what I call an amateur method which is also very much a queer method – around that expertise as I grappled with this membrane between the public and the private. It was very daunting writing the book because textiles consume so much of our lives; it was a bit torturous to decide what precisely to focus on.

I like that you decided to focus on the Neo-Liberalism connection between the US and Chile. I wondered how you made your choices for the chapters.

I just did a book talk at the Courtauld Institute in London, and the first question from the audience was ‘why didn’t you talk about the UK?’ So I’m thinking that will be Fray: Volume Two (we both laugh). But seriously, you cannot take on everything given that it is such a vast subject, and I decided to write about objects that I knew personally or that I had had an encounter with.

And, what’s next?

I’m writing a book about Louise Nevelson. She created an all-black sculpture for over forty years and I am fascinated by her use of the monochrome and her use of wood.

You can learn more and purchase Fray via The University of Chicago Press website.