Switzerland: Water on the Moon

Travel — 07.03.19

Photography and writing by EXTRA HANDS

(Lindsey Shorter & Blake Shorter)

This should be made known: what the Swiss describe as a ‘walk’, most anyone else would call a ‘hike’. Maybe even a ‘moderately strenuous-to-difficult hike’ – these thoughts were playing on a loop while ascending the long gravel trail en route to the basin at the foot of the Ferpecle glacier in southern Switzerland; then, our perspective shifted to curiosity and wonder as we entered the valley and the landscape began to change. Pale green and velveted and dense with trees and shrub, the forest cut narrowed, and pine needles carpeted the path beneath our feet. The weight of the bottle of French wine and the film cameras and books in my pack (the essentials) became more of an afterthought when we heard the growing white-noise static of the glacial river, moments before it came into view. The brush cleared and was replaced by short, dry grass dotted with massive head-high boulders that begged to be scrambled atop: the perfect spot to perch and take in the panorama of the surrounding lunar tableau. Continuing into the valley, the river beside us calmed to a gentle crawl and the soil turned from gravel to sand – the pale blue water was chalky with mineral-rich Silt.

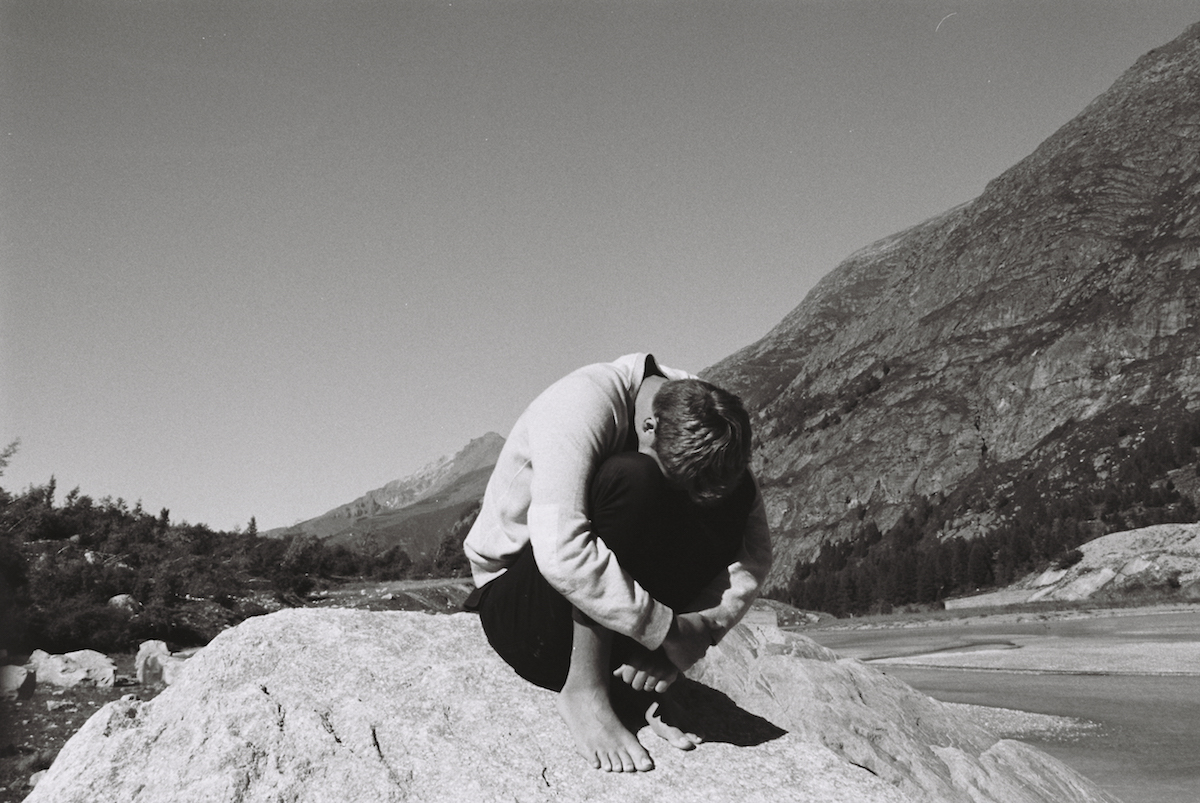

First thing, take off the bag and let the wine and our water bottles start to chill in the water (the water must have been just above freezing, it was numbingly, intolerably cold). Then, unpack our picnic of cheese and olives, saucisson, and bread and mustard, which had become a staple of our diet while in France for the previous two weeks. Boots and sweaters came off; it was September, but the sun was shining, and the mountains that enclosed the valley on three sides protected us from anything more than a gentle breeze.

All around us were mountains, a cul-de-sac of ten-thousand-foot craggy peaks, and the glacier that reflected the sunlight and slowly trickled icy water down into our celestial pool. We ate lunch in the shade between two huge rocks – it was difficult to talk about anything more than the spectacle of where we were. A place like that, so far from home and so geographically & topographically foreign and raw, inspires a sense of awe and forces the visitor to pay attention. I don’t remember ever thinking about my phone.

After lunch, we lounged at the foot of the water and read and hand-rolled a cigarette – we were on holiday. Peace, like a river. As we drifted into restfulness, we heard a muffled crack and rumbling sound, and we shot up and looked in the direction of the noise. A cloud of snow was rolling down from the top of the glacier, a literal avalanche – but the foot of the glacier was still a few hundred meters away from where we stood, and alarm faded as the snow settled and the white cloud dissipated. Maybe in the dead of winter, when the snow is stacked tall and deep on the mountains, perhaps then we would’ve had real trouble. We went back to reclining in the sunshine but quickly grew restless to explore. We walked in the shallow water and rubbed mud onto our faces and hopped from rock to rock. It’s very important when given the opportunity, to try and remember how it felt to be a child.

In the book “How to Change Your Mind”, author Michael Pollan writes that travel can re-wire your brain, especially when you’re confronted by an experience that’s completely new and unfamiliar. That afternoon, laughing and talking and just sitting and looking at the surrounding natural beauty, it felt like my brain was de-tangling itself. The knots of confusion and frustration with life and work and pressures and expectation and insecurity and anxiety were coming undone, and there was no thinking – it was the experience of being present.

The sun eventually fell behind the mountain, and the shadow slowly swept down the mountain opposite it, then across the glacial water, and then over us. It felt like a natural close to the afternoon in the valley, and as the air grew colder around us, we began to pack up our bags. On the way out I couldn’t help but to scramble up one last boulder and pose at the top, yelling for my partner to take a picture.

As we began to retrace our footsteps out of the valley, we noticed another trail that was going in the same direction but closer to the river, so we took it. Over the hum of the water, we heard the sound of bells and looked across the river to see a small herd of alpine cattle: Heréns, a breed specific to the glacial valley. There was an old footbridge ahead, crossing over the water, but a wooden plank had been nailed crossways to the opening of the opposite end of the bridge to make a fence. Assuming that the fence was built to keep the cows out rather than to keep us from getting in, we hopped in and made our way cautiously over.

The cows didn’t seem to mind our approach. We spent a few moments standing quietly with them, observing the slow and measured movement of their massive bodies as they grazed on the alpine grass and shrubs, sometimes pulling the needles straight from the branches of smaller larch trees and chomping away methodically, staring off into the distance at the grand view of their monumental backyard.

When the last wave of warm sandy light receded from the meadow and was pulled upwards towards the mountain tops, the herd turned as one to follow it and began heading up the hill and in the direction of a small and ancient-looking barn. The soft exit of the animals seemed to signify that it was our cue as well and turning to cross over the wooden bridge, we began walking, back in the direction we had come.